Figuring out 'dpi' turns out to be a big deal for a lot of people, at least that's what I've found in my digital imaging seminars at Vashon Island Imaging. Maybe I'm expecting too much. It took me a while to get it, truth be told.

I got in on digital imaging with PhotoShop® version three back in the last century. It's impossible to explain how 'simplistic' things were back then, and still are for many but for entirely different reasons. Back then there was no such thing as giclée. Things like resolution and dpi weren't on your mind as much as just getting enough RAM to run the program. Now, memory is cheap and machines are fast. The constant migration towards simple-to-use, automated algorithms eliminates the need to think of size in pixel terms. When I post by this blog, for example, I can upload any size picture and it will automatically be re-sized for my template... no math required. As a result of such automation some people don't understand dpi.

At Vashon Island Imaging, my fine arts printing and publishing company, a common problem is customers who prepared their pictures to the desired size but at screen resolution (72 dpi). It takes a lot of explaining to make them understand that the picture isn't the same size in the world of giclée.

What really boggles the 'pre-get-it mind' is that something can be one size one way and another size another way. It doesn't even read right when you write it. However, size matters when it comes to pixel perfect printing.

Pixel perfect printing is when you are in control and getting the results you are after. Control is when you make the decisions instead of the device(s).

There's nothing wrong with automation and algorithmic image making. Very likely automated systems take better pictures than some people ever will. I will grant you that. But 9 times out of 10 you are going to produce a much better giclée if you know how to turn the dials yourself. That involves knowing not only what the dials do, but why you are doing it.

There are many ways to 'darken' a picture, for example. Which one should you use and why? The answer might come from which varnish will be used to finish the giclée. Or using a This Old House metaphor, there are many ways to approach the restoration or salvage of image files that are in need of repair.

It is difficult for the average PhotoShop® expert to know what is necessary to make a good giclée print, unless they do a lot of their own printing. Apparently many of them don't because there are few other books on the subject of giclée prepress and other PhotoShop® manuals don't get into it prepress at all, really. That is why there is a disconnect between people and their printers.

The disconnect is an information gap about how to prepare pictures for the extremely high quality that giclée printers can deliver. People finish their picture in PhotoShop and expect that when they push the print button out will pop the perfect print. When it doesn't come out right, they don't know how to fix the problem because they don't know the cause. They see a result without knowing what produced it. That is why I wrote the book (and why I write this blog). You may have total control over PhotoShop®, but what about your printer? If you don't have a printer but instead take your pictures to a print shop, how do you get control of something you may not have? Aviation provides one example of how this can be done.

How do they train pilots? In simulators. What do pilots look at in the simulator? Screens... monitors. That is what your monitor is... a simulator. And that is what PhotoShop® is for a giclée prepress artist. The difference is that a giclée prepress artist knows what to look for on the monitor screen. That is what I go into detail about in Giclée Prepress - The Art of Giclée, my book on pixel-perfect printing (www.gicleeprepress.com). But I digress. Let's get back to numbers.

When you avail yourself of the convenience offered by automation, your images will suffer because algorithms 'average'. Averaging is what the census people do with folks like you and I. Unless you are an Einstein or the village idiot, you're average. But what if you want above average results? In some cases you can tweak the algorithms with profiles to get the results you want. You may be happy with the picture(s) but wouldn't it be nice to know exactly why they got that way? After all. they don't let pilots fly real planes until they have control (we hope).

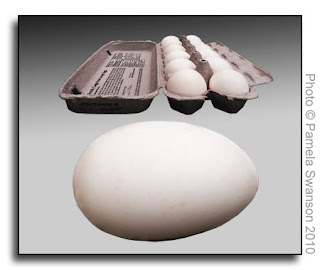

Let's assume you're like me, not Einstein. Even for you it probably makes sense that you cannot put thirteen eggs into a one-dozen box. That's why numbers are important in printing. If you send a 100-color printer 200 colors, something's gotta give. The question is, who makes the decisions about what stays and what goes? It's not about crop. It's about pixel density.

A giclée print is like a box. The bigger the giclée, the bigger the box. Each box holds a certain number of pixels when filled to capacity. If your print needs 1200 pixels and your image file has 1300, the printer algorithms will take your ingredients and make 1200 pixels out of them. If you have too few pixels, the algorithms will invent the number needed to fill every space in the box. In both cases, your pixel information changes because original pixels are combined with one another to create the re-sized result... like blending paint. Re-sampling is what people call that process. Purists hate it.

To some extent, re-sampling is unavoidable. You are going to make various sized versions of pictures. The question is, which software will do the re-sampling best and will the picture need any further adjustment after that?

Re-sampling is best done by the original artist on the same machine that built the original image file and seen on the same monitor during the picture's development. What you want to avoid is a different type of device re-sampling the image without any chance to make final pictorial adjustments to the re-sized version before output. In simple terms that means it is better for you to size the pictures than have the machine do it for you.

All this holds true in audiovisual work as well. In the AV world it is even more important to feed each display with images that fit within its native resolution. Sluggish performance and aberrations like 'tiling' are otherwise encountered as those devices must render 'on the fly' ... they don't have the luxury of time to do the calculations, like a giclée printer does.

Your giclée printing machine has enough work to do recalculating colors into its own gamut, adjusting for particular media and possibly changing schemes from RGB to CMYK. Don't exacerbate the complexity of calculations by introducing pixel density changes into the equation.

If you are printing your own work, you can find out the pixel density of your machine from its manufacturer. For example, my big Epson prints at 240dpi so the picture-size math is based on that number. To make a 10 X 10-inch giclée, 2400 X 2400 pixels are needed.

Most publications and publishing software suggests 300dpi. That density has become the default 'standard size', which is perfectly fine because that density exceeds the requirements of most output devices.

The web's audiovisual density standard of 72 dpi is where the real problems begin. Those super-small sized images don't have enough pixels to make large giclée prints of high quality. To scale up small web pictures into large size giclée prints there are many adjustments to improve the looks which are described in my book.

Whether too few or too many, it's not just a question of how you measure up, but who will do it. If you don't do it that leaves only two other possibilities... a giclée prepress artist or the printing machine. The choice is yours. At Vashon Island Imaging we'll give you first-class giclée prepress and/or teach you how at seminars on digital imaging. Or take a look at the book. There's a good-sized preview at www.gicleeprepress.com.