Servicing sexagenarians has become a hot business for us at

Vashon Island Imaging. The Viagra® crowd brings us faded family photos to be restored before precious memories disappear. We put the 'snap' back into their snapshots and provide the client with both a digital file and a 5 X 7 inch print (12.7 X 17.78 cm) at a price they can't refuse.

Restoration is an offshoot of prepress work. It is business we are encouraging because it is great filler work and highly profitable. Consider that 90% of the job ticket is billable hours, which go straight to the bottom line. However, to make money you have to work fast because people don't have unlimited funds for restoration work these days.

Family albums are low hanging fruit for prepress artists like me. Think about it... Older folks saved those albums for exactly this time of their lives. Imagine their distress when after all these years they open the album to find that the pictures have their own version of Alzheimer's and that their memories are fading fast.

These same people are concerned about their legacies. Those family pictures were supposed to be passed on through future generations, but they will never make it in their current form. Most of them are aware of digital solutions for archiving pictures, like CD's and optical drives, but they are clueless about where to take their family snapshots to have them rescued from the ravages of time.

I'm a sexagenarian and have watched time ravage my own picture archive. Black-and-white negatives and prints are holding up well (as expected). However, anything color is in deep trouble, whether slides or prints. Color slides and negatives have two enemies, unstable dyes that fade, and 'protective' plastic pages that melt away releasing oils that stain and permanently damage film emulsions. (The plastic pages sold for CDs also have this problem after only 15 years.)

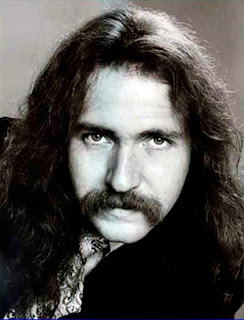

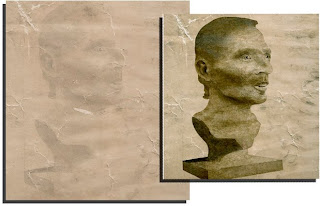

This 1973 portrait of yours truly taken by Dona Tracy hasn't changed much over the years. Either have I (ha ha). It was printed on Kodak® Kodabromide paper processed in Dektol developer, the combination used at Life magazine photo laboratories back in the day.

This 1973 portrait of yours truly taken by Dona Tracy hasn't changed much over the years. Either have I (ha ha). It was printed on Kodak® Kodabromide paper processed in Dektol developer, the combination used at Life magazine photo laboratories back in the day.How well 40 to 50 year old color prints in my archive have survived is all over the map. Mind you, although my archive isn't kept in a humidity and temperature controlled environment, I live in a temperate zone without extremes and the work is kept in very subdued light. Dye transfer prints have survived in good shape. Kodak® Type-C prints (printed from color negatives) are borderline and have that 'old' look about them. Kodak® Type-R prints (a color-reversal process made for printing slides) are badly faded. The worst are old Polaroid® prints, which turn pink as their cyan dyes disappear.

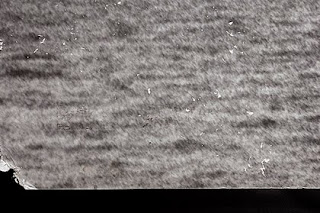

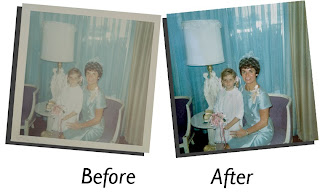

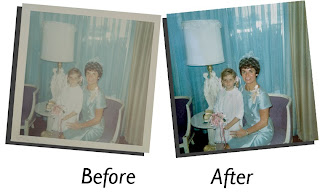

Polaroid® print from 1961 shows degradation of all dyes, particularly cyan.

Polaroid® print from 1961 shows degradation of all dyes, particularly cyan. Kodak® Type-C print has lost its cyan dye but the magenta and yellow have held up pretty well. The total lack of cyan information makes the restoration of accurate original color dicey.

Kodak® Type-C print has lost its cyan dye but the magenta and yellow have held up pretty well. The total lack of cyan information makes the restoration of accurate original color dicey.The problem is like disappearing ink... a time bomb. But folks can't hear it ticking because after all, how often do you open the old family album these days?

Chances are none of this is or will be of any concern to you until you too, are a sexagenarian. But guess what?

Sexagenarians are the leading edge of the 'baby boomer' tsunami that has reached our shores. There are an unlimited number of family albums out there begging for affordable restoration. Once the word is out that you provide such a service, watch what happens... your dance card will fill up fast. That is why we offer sexagenarians sizzling deals they can't turn down.

Piece Pricing Is PreferableWe try to keep the price to about $15 per picture, including a 5 X 7 inch (12.7 X 17.78 cm) print. Keep in mind that we are talking about snapshots here, so in comparative terms a 5 X 7 is big. Some folks end up getting bigger sizes needless to say. However the printing is the smallest part of the job. Some customers aren't even interested in prints, as they are more interested in the digital files of the restored images. In those cases you have no job costs at all.

Our customers set the $15 price for the snapshot service. Formerly we tried working at an hourly rate but that seemed awfully high to our customers. If you quote $50 or $75 an hour folks get nervous. But if you point to a snapshot of their Mom and ask for $15 that seems more reasonable.

There is no clear relationship between the $15 price and our normal hourly billing rates. To make our targets we've got to process five snapshots per hour. Sometimes that is possible, but often the throughput is less. I just finished a job with an average speed of only two per hour... or $30. However, that's the exception and I should have seen it coming (read on).

Knowing when to stop is the key to making money. Restoration work is like a hike in the woods. You can go forever. If you are like me your heart is with the picture not the price. I always put in more time than I should, however that is my way of giving back to the customer. In today's economy it is better to extend service than to cut price.

'Twice as good' is my mantra while I'm working on family album restoration work. Each restored picture should look twice as good than the original. That too is an imprecise measurement, but you get the idea.

It may well be that the pictures you are working on will have mostly $15 price tags with a few that costs $20 or $25. Whatever, with piece pricing the customer has an easier time deciding.

Importantly, take a very close look at each snapshot you are servicing. If some of the pictures look problematic take time to explain that to the customer. Point out any unusual problems. That job I just mentioned, that took an extra long time, should have been $25 or $30 each since the throughput rate was 2 per hour.

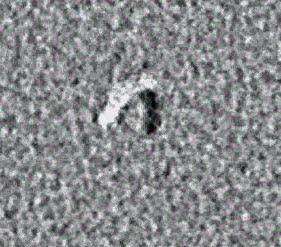

Extreme close-up of black fibers embedded in picture's emulsion. They are from the album paper and are the result of compressed storage in a humid environment. Many albums end up in the basement or an unheated attic at the bottom of piles being squeezed hard by the weight of the stuff on top. Dried glue drops, tape and those 'corners' they sell for albums create high points that can push paper fibers into the soft emulsion surface of old color prints.

Extreme close-up of black fibers embedded in picture's emulsion. They are from the album paper and are the result of compressed storage in a humid environment. Many albums end up in the basement or an unheated attic at the bottom of piles being squeezed hard by the weight of the stuff on top. Dried glue drops, tape and those 'corners' they sell for albums create high points that can push paper fibers into the soft emulsion surface of old color prints. This time I didn't look closely enough to notice a huge problem, however.... the album pages had shed black paper fibers which had became embedded in the emulsions of certain prints (especially Polaroid® prints). On others, the glue from one side had seeped through stained prints on the other side.

The fibers turned out to be so embedded that some were impossible to remove. Using cotton swabs with a variety of solvents did nothing, and water softened the emulsion so that it wiped away with the fibers, as shown above...yikes!

The fibers turned out to be so embedded that some were impossible to remove. Using cotton swabs with a variety of solvents did nothing, and water softened the emulsion so that it wiped away with the fibers, as shown above...yikes!  Yellow stain of chemical migration from glue has been intensified for easier recognition. Seepage is aggravated by humid conditions. Nice fibers too, eh? It was lots of fun removing those, let me tell you.

Yellow stain of chemical migration from glue has been intensified for easier recognition. Seepage is aggravated by humid conditions. Nice fibers too, eh? It was lots of fun removing those, let me tell you.  A scouring pad sponge turned out to be the solution for removing the fibers. Only certain types work on pictures. NOT the ones that are green and yellow and meant for scrubbing pots! The scouring pad part must be a soft plastic so that it doesn't scratch the surface of the prints. Using this sponge I was able to get rid of 90% of the fibers by rubbing hard in a crisscross pattern Restoration Is Prepress On Steroids

A scouring pad sponge turned out to be the solution for removing the fibers. Only certain types work on pictures. NOT the ones that are green and yellow and meant for scrubbing pots! The scouring pad part must be a soft plastic so that it doesn't scratch the surface of the prints. Using this sponge I was able to get rid of 90% of the fibers by rubbing hard in a crisscross pattern Restoration Is Prepress On SteroidsTechnically speaking, restoration work is not prepress.

Prepress is the adaptation of an image for a particular type of output. It does not generally involve changing the picture, although I stretch that definition in practice every day of the week.

Vashon Island Imaging is known for making pictures look good and that usually means 'intensification' of the image to extend its dynamic tone range.

The techniques used for restoration are actually the same ones used for general prepress work for giclées. You could say that restoration is prepress on steroids. Such work is described in detail in my book,

Giclée Prepress - The Art of Giclée and in prior blogs. Following now are some techniques for servicing snapshots:

As Similar As They Are Different

Old snapshots are different from one another and have inconsistent tonal qualities. However, they share common aging problems so you'll find yourself doing the same things over and over, and after a while the work goes fast.

You may even be able to make PhotoShop® Actions for the most basic adjustments. That's because all pictures of a certain type share the same problems. An old Polaroid® may have completely different problems than other types of color prints, but all old Polaroid® prints have the same problems.

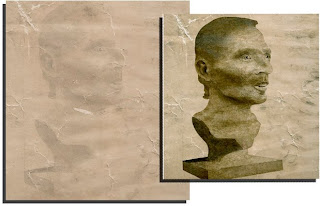

This old black-and-white print didn't fade with age. It was originally a badly underexposed picture printed on contrasty paper. These kinds of problems are not difficult to fix.

This old black-and-white print didn't fade with age. It was originally a badly underexposed picture printed on contrasty paper. These kinds of problems are not difficult to fix.Old black-and-white prints present their own rainbow of challenges but they are generally not time or age related. Black and white images are made of silver particles, which are relatively inert. Instead the problems you encounter with old black-and-whites is poor photography combined with bad processing.

This old Polaroid® print is brown where lack of proper fixing left silver salts that have oxidized into brownish shades. Remember those smelly fixative wipers that came with the original black-and-white Polaroid® film packs? If you didn't wipe completely, covering the entire surface with the fixative, this is what happens.

This old Polaroid® print is brown where lack of proper fixing left silver salts that have oxidized into brownish shades. Remember those smelly fixative wipers that came with the original black-and-white Polaroid® film packs? If you didn't wipe completely, covering the entire surface with the fixative, this is what happens. Compounding the restoration may also be physical damage. Some glues, pastes, papers and tapes leave chemical stains, as I have come to discover.

The result of all these assaults is an album full of photos that are:

● Faded

● Poorly photographed (over or under exposed)

● Unevenly lit (especially flash photos)

● Badly processed (motley degradation)

● Damaged by water, tape, tearing or other

What a treasure trove for a prepress artist, eh? If you decide to have at it, here are some easy techniques we use at

Vashon Island Imaging:

Capture Highlight & Shadow DetailsWhen copying the snapshot, under expose the capture so there is no white. The white parts of the picture should be 10% gray (at least).

If it is a dark picture make an alternative over exposure in which all blacks are 90% gray. If you use more than one exposure, combine the best parts of both into a single layer.

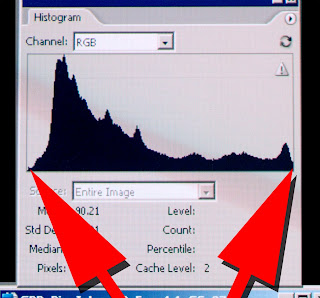

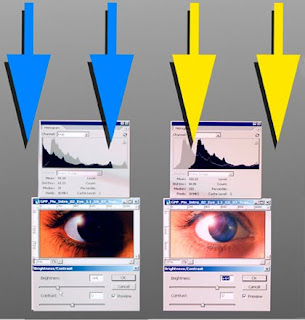

On the left is how the image capture should look as you begin your prepress work. Whites should be grays at this early stage of production, making available a wider assortment of adjustment tools that will not respond to white.

On the left is how the image capture should look as you begin your prepress work. Whites should be grays at this early stage of production, making available a wider assortment of adjustment tools that will not respond to white.Working in grays is better than whites at this stage. It is easier to pull white out of gray than the other way around. For example, if a face is blown out or faded, under expose your capture so that white is 10-20% gray, then lighten the whites of the eyes and teeth. Subtle use of the Dodge and Burn tools will allow you to contour highlights in the light gray tones. You can only do that if the white point is low enough to begin with. And as I say, it is easier to lighten gray than to darken white. Whites have no data so there is nothing to work with.

Light gray tones are also more adjustable with both mid tone and highlight controls. The lighter the gray the less it responds to mid-tone adjustments.

Clean & Spot CaptureStart prepress work with a thorough cleaning, removing any dust & scratches or other mars. There are usually plenty of those in old snapshots so this part of the job can be tedious. Concentrate on the most important parts of the pictures, their subjects, and work your way out from them. I use the Rubber Stamp clone tool for that job.

Duplicate that picture layer and get it cropped and sized. If you included a gray card in the picture keep a bit of that gray in the frame (crop it out after color adjustment).

The lowest layer in the stack should be the original image. It's there for back-up so you can switch it off and forget about it. Consider the duplicate picture layer as the new original.

Set Levels and White PointUse Levels and get the picture looking as balanced as you can. I often start by using Auto Levels to see what PhotoShop® has to think about the situation. About 25% of the time I agree and keep that version on a separate layer, if only to cannibalize it later. Quite often using Auto Levels provides a great starting point for further Levels adjustments. I like my pictures darker and warmer than the folks at Adobe and I have an Action that copies the Auto Levels layer and applies a Brightness setting of -22 (moves the white point to gray).

Use the Burn and Dodge tools to bring out the most important parts of the subjects in the picture. If they are faces, intensify the eyes and make sure that the whites of the eyes (and teeth) are white enough. De-saturate and adjust the brightness of those that aren't.

Do all burning, dodging and tone 'depth' adjustments before making color adjustments. Reversing the procedure can alter the colors.

Make Color Adjustments After Tone Depths Are SetNext I use Auto Color and am frequently surprised to see PhotoShop® deliver an entirely different interpretation than the Auto Levels or Auto Contrast adjustments. To see for yourself, do Auto Color first one time, and Auto Levels first the next time. What works best in my opinion is Auto Levels first, followed by Auto Color which usually makes the picture slightly less contrasty and a little warmer.

If you use Auto Color on a separate layer you can combine the best parts of the Auto Levels layer with those of the Auto Color layer. If you make such a combination, re-visit Levels for a final tweak.

Sharpen Resulting ImageWhen you are happy with the result, make a duplicate of that layer and sharpen it using the Unsharp Mask tool. How much? That's a matter of taste however for a file that is about 2,200 pixels on the long side settings of 2.2 / 222 are not unusual. That may seem extreme but the 5 X 7 inch (12.7 X 17.78 cm) giclées will look outstanding.

Another technique is to make additional layers and sharpen them to varying degrees, then re-combine the best parts of those layers. This is a good trick for portraits, making the eyes sharpest of all.

Changing the Opacity levels of various layers can further tweak the look, as can adjustments to their Blending Options (lighten & darken).

Clean and Blend Sharpened ImageNo matter how thoroughly you spot and clean a picture, when you sharpen it more spots and scratches appear. Thus, after sharpening you may have some more spotting and cleaning to do. Try the following procedure to quickly get rid of the light spots.

1.) Set the sharpened layer's Blending Options for darken.

2.) Adjust mid tones of the un-sharpened layer beneath to 1.07 or so

In this way the softer pixels below fill in the lighter sharpened ones above making most of the objectionable light-colored spots invisible. The reverse holds true for getting rid of dark spots. Merging the results of both procedures reduces the need for laborious spotting with the Rubber Stamp tool.

Not that you will entirely escape the drudgery... Some handwork is always needed after sharpening. Don't forget that you can set the Blending Options for the Rubber Stamp, which can make spotting go way faster.

Creating Repair PatchesIf there's a section that is unusually dusty or dirty, replace it with a repair patch made by airbrush work or blur tools.

1.) Copy offending part of image onto a separate layer.

The copied section of the picture will be converted into a repair patch by defocusing it using Blur tools.

2.) Place repair patch layer beneath image layer.

3.) Apply some Blur to the repair patch (Gaussian Blur, Surface Blur, etc.).

Alternatively, select the offending area and airbrush over it on a separate layer. (To get the paint colors right, sample the image with the Eye-dropper tool.) Then...

4.) Set the Blending Options of the image layer on top to darken.

5.) Adjust mid-tone Levels of the patch underneath to about 1.07, (slightly lighter).

Adjusting the Levels of the patch gives you control of the amount that the patch shows through the image, which has its blending set for darken. The light spots in the sharpened layer can't darken so the patch shows through, filling in the light-colored crap in the sharpened layer. Reversing the procedure also works.

Use Noise to Recreate Grain & Digital TexturesSevere problems may require that repair patches be placed over the image layer to replace entire sections, not just the spots. Any airbrush work you do lacks the 'grain' texture of the original image. Lacking that texture your retouching stands out like a sore thumb.

The fix is to recreate the look of the grain by adding noise and then blurring that noise. The size and type of noise must be precisely adjusted in combination with the amount of blur. It's a little fussy but with those adjustments you can recreate the look of almost any type of film grain or digital texture.

You're As Good As Your Last PrintAlthough they probably wouldn't admit it, when our colleagues and customers see our work the first thing they look for are problems. Once satisfied that there is nothing wrong, they relax and enjoy the fruits of our labors.

There's always a client that will insist on making a change, usually as some sort of power trip. But hey, it goes with the territory. Once a client has been identified as being a 'helper' all future work we do for them contains red herrings.

99% of the time our clients are blown away by what we do with pictures that looked lost. Sometimes I am surprised myself to see how basic prepress can bring pictures back from the dead.

One of my earlier blogs details the account of restoring a picture washed away in Hurricane Katrina. That picture (seen above) took days, not hours, of tedious detail work. To keep from getting discouraged, remember that this job is an advertisement about you... so it better be good!

When clients are pleased I like to say,

'Ingen Kunst Als' a Swedish expression with a double entendre. As slang the expression means, 'Nothing to It'. Literally translated it means 'No Art At All'. Being an artist, you can appreciate the irony.

Making snappy snapshots for sexagenarians may not be as sexy as printing fine-arts giclées. However, restoring humble snapshots and memories thought lost brings smiles (and checks) that are just as big as those we earn for fine art.

Most people place the gang-up in the center of the sheet, stacked. That makes visual sense... it looks balanced. Anyway, that's most people's placement choice. They also leave some space between the two cards ...they are separate cards, right?

Most people place the gang-up in the center of the sheet, stacked. That makes visual sense... it looks balanced. Anyway, that's most people's placement choice. They also leave some space between the two cards ...they are separate cards, right?

I've been making dummies for more than 40 years. Burt Holmes showed me how when I was his assistant at Basford Incorporated, an industrial advertising agency in New York, in 1966.

I've been making dummies for more than 40 years. Burt Holmes showed me how when I was his assistant at Basford Incorporated, an industrial advertising agency in New York, in 1966.